In 1850 Milo Smith, a Mount Washington farmer, was sowing grain on his property when, in his words: “Up drove a four horse team to the door. I was out at the barn, and they followed me around, and nothing they could do but they must stay overnight.”

His visitor was Elizabeth Sedgwick, arriving with fifteen students from Miss Sedgwick’s School for Young Ladies in Lenox. Somehow Milo found room for his unbidden guests, who then “carried their dinner with them, and went up on top of the Dome. The next day they spent over at the falls, and then went to Salisbury.”

This rather peremptory visit marks the beginning of tourism in the South Taconics. The Dome (Mount Everett) and the falls (Bash Bish) remain the most visited spots in the mountains, although no-one drives four horse teams up the roads any longer. Without planning on it, without advertising at all, Milo became the first keeper of a Mount Washington boarding house.

The first dollar that Mount Washington resident Isaac Spurr earned after turning 21 came from Miss Sedgwick who “hired me to leave the coal bush” and “pilot them to the top of the Dome.”

The image of Spurr, setting down his charcoal rake and hiring as a guide to a remote beauty spot, helps me imagine the “nature” these first seekers found in the Taconics: clear-cut openings in the woods, charcoal circles, deep-rutted wagon roads, eroded pastureland … along with deep forests, clear streams, vistas worth a tiring climb.

But the boarding houses boomed. A crucial turning point: 1852, the opening of the Copake Falls station of the Harlem Valley railroad. This allowed farmers — badly in need of extra income — to set aside a few rooms, advertise in city newspapers, and pick up guests at the station for a mountain carriage ride to their vacation stay. Mount Washington’s population peaked at 438 in 1840, but in 1887, ten boarding houses operated in a town with a population of around 180. This decline seems unsurprising given the collapse of the sheep boom and the waning of the iron industry. So boarding houses may have been crucial in preventing the town from fading even further.

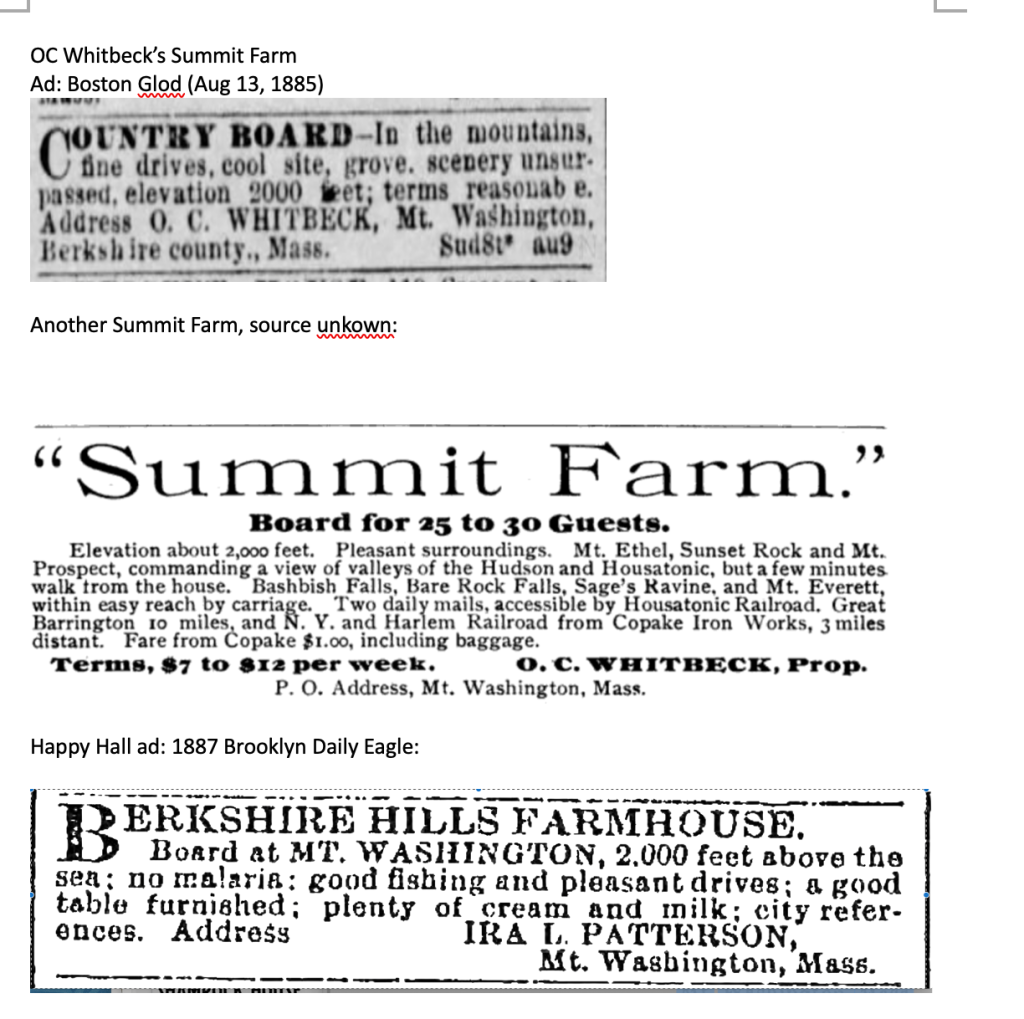

Consider that in the 1880s, O.C. Whitbeck, owner of Summit Farm on West Street, charged $7-$12 per week for room and board (and .75 for the trip from Copake.) Say on average a guest paid $9 per week; say the house reached its capacity of 30 for only 12 weeks out of the year. (A low-ball assumption; many houses were booked solid by January.) This would bring a yearly gross of around $3,000. Now consider that according to the 1880 agricultural census, Whitbeck’s farming activities earned him a total of $500. You’d have to subtract some overhead from that $3,000 figure — Whitbeck must have needed help to accommodate 30 guests — but much of the food was grown on the spot, and the main attraction, natural beauty, was free of charge. It seems plain that Whitbeck, like many of his mountain neighbors, was earning his chief livelihood by selling (as advertised) “fine drives, cool site, scenery unsurpassed” and not farm products.

The charms that drew this yearly stream of visitors may seem awfully plain to 21st century tastes. How did they pass those long summer days? They swam. They played badminton and croquet. They ate three big meals of farm fare per day. They fished. They hiked. They embarked on long carriage rides. In the evenings, one guest might play the piano while others sang or danced.

To my mind, tuned to a barrage of digital distractions, it sounds relaxing. I’d like to travel back to Taconic Farm in July of 1890 and pass a rainy Friday “by a dance in the barn to the tune of a piano over 100 years old, a cow bell of uncertain age and other musical instruments of various kinds.” Or spend an evening at OC Whitbeck’s farm, enjoying music for dancing by the Doty Brothers, as well as Arthur Whitbeck’s “remarkably fine voice.”

These simple pleasures sometimes attracted notable guests. Milo Smith boarded Herman Melville and his wife, as well as the renowned lawyer Dudley Field and the British actress Fanny Kemble. Ray Ditmars, head of the Bronx Zoo’s herpetology department, stayed at the Pennyroyal, collected rattlesnakes, and reportedly stashed one in a drawer. A Barnum and Bailey circus clown was also a Pennyroyal guest, along with a couple who, for religious reasons, never spoke. Many guests were repeat visitors for a string of summers: in the late 1880s, a Mrs. Janes’ stay at Cottage Farm continued a tradition begun when she was a girl.

No mountain biking, long distance running, or ironman training in the 19th century; still, a few intrepid souls pushed their limits. The periodical Student and Schoolmate in 1869 carried an account of a climb by two young men who set out from Sheffield, in the snow, on a vague trail along the “Mosskill.” (A name that hasn’t survived the years.) They reached the top of the ridge “… which, with lowering clouds and huge rocks around, seemed like entering the very gate of heaven.” They climbed Bears Cliff (which would place them near Plantain Pond) and entered “a community separated from all the stirring scenes of life” — Mount Washington. Slipping on ice, sprawling in water, they rejoiced when they spotted their destination — a “farm house of moderate size, painted white, its gable end facing the road” — Milo Smith’s.

Another appeal of mountain visits — health — reminds us how different the parameters of nineteenth century life were. Consumption (tuberculosis) and malaria were everyday threats; mountain air might be a preventative or a cure. One doctor warned that “Malaria since 1877 has reappeared in swampy areas,” but assured his audience that sites in the Taconics were “protected from superabundant moisture of east wind by mountains.”

Could the mountains also enhance what we now call mental health? A sales flyer for the Berkshire Hills Park Association declared: “The brain worker must have occasional recreation in the form of full contact with nature or else must inevitably succumb to vague ailments if not to positive and incurable disease.”

Each boarding house had a distinct personality and history. The busiest proprietor may have been Whitbeck, who in the 1880s, along with running Summit Farm on West Street, served as Mount Washington selectman, town clerk, surveyor, tax collector, and editor of a town newsletter. The civil engineer and historian Herbert Keith, whose papers I’ve spent many hours exploring, owned Taconic Farm (also on West Street.) The Pennyroyal Arms, which still stands on East Street, boasted a library with its own card catalogue, and rules to be “strictly observed.” (“Books returned, must be cancelled in Register, and placed in Book Rack on Library Table.”). The owners of Cold Brook Farm on East Street also operated a Tea House, across the street from the present-day entrance to the Mount Everett Road. Here “Every detail is personally supervised, from abundant, delicious food, to the attractive service on lovely old china, silver and fine linen.” The Alander Hotel, which rose near the present day State Forest Headquarters, could hold up to 50 guests.

But attention must be paid to those who were not invited to enjoy the mountain air: black people and Jews. By the 20th century this ban had to be expressed in code: “exclusive clientele” meant “whites only.” Many proprietors claimed they were only catering to the prejudices of their guests; nevertheless the mountains were in effect segregated.

It didn’t take long for some visitors to become semi-permanent residents. Herbert Keith states that the first “city person” to purchase a residence in Mount Washington was a music teacher named Mrs. Walsh and her husband, an apothecary. They threw a party for their workmen shortly after their house near Guilder Pond was completed; sadly, Mrs. Walsh soon caught cold and died. But in short order P.C. Garrett of Philadelphia built a “fine cottage” by Lee Pond, and Keith estimates that by his day — around 1915 — non-residents controlled two-thirds of Mount Washington real estate. An 1883 article promoting “Berkshire as a Health Resort” proclaimed that “The preference for a residence in the country by persons of taste and refinement is rapidly gaining strength among Americans as it has long been characteristic of our English kinfolk.” One manifestation of this trend in Mount Washington was the above mentioned Berkshire Hills Park Association. Promotional materials describe a long search for an appropriate site for a recreational community that ended with the discovery of the old Wright farm, near a branch of Bash Bish creek, where “..to our delight and wonderment, this neglected region proved to be an ideal locality.”

As the 20th century progressed, second homes steadily replaced the boarding houses. The 1972 closing of the Copake Falls train station was only a late signal that an era had passed; car and air travel had long since opened choices that left the days of croquet and carriage rides far behind. The last boarding house closed in the mid 1980s.

No cell phones in the 19th century; no laptop computers. Still, it’s striking how 21st century voices bemoaning the speed and stress of modern life are echoed in the19th. One writer glorified Mount Washington for everything it was not: “Less of the friction of life one could hardly hope to find than in this mountain town. Here is no railroad station or express office, no telegraph office, no store or manufactory of any description, no grist mill, no blacksmith shop, no brass band, no resident lawyer, doctor or clergyman.”

Of course, grist mills and blacksmith shops were once very much part of Mount Washington life. The charms this writer celebrates were due to the process, still apparent today, of an economy based on iron, lumber and farming giving way to an economy based on relaxation and scenery.

Boarding houses were just one example of this new way of using the mountains. The Catamount ski resort, on Mount Fray, opened in 1940 (with three rope tows and a 40 by 47 foot lodge.) Today it boasts forty-four trails, a new lodge, four grooming machines, and zip lines for summer visitors. Jug End resort opened near the base of Mount Sterling in the mid 1930s, grew to accommodate a heated swimming pool, tennis courts, a trap shooting range, a golf course, ski lodge and snowmaking, but succumbed to bankruptcy in 1983 and is now a State Reservation.

Then there’s the star of the South Taconics, Bash Bish falls. It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth century that this gem gained a wide reputation. The survey notes on an 1830 map of Mount Washington describe the upper gorge as a “dismal chasm” but an 1854 poem by E.M. Powers has a different perspective:

“Great nature’s holy place! Here let me lean

Above this dizzy cliff, in Summer ease

And taste the glory of this matchless scene”

Charles Blondin, a famous French tightrope walker, was invited to cross above the falls in 1858, though it’s not clear whether he accomplished the feat or was deterred by the boulders awaiting him should he slip. (He definitely did, however, walk a tightrope over Niagara Falls.)

An inn gazed down on the falls from 1879 to 1894, run by the Douglas family who had acquired most of the property extending back towards the Copake Iron Works. On ground across the stream from what’s now the lower parking area, they built a Swiss style chalet with numerous outbuildings, and this became an inn run first by the Vacheron family, and later by a New York City chef named Louis Maquin. But in 1918, this structure burned to the ground, and in the 1920s the land became a car campground.

Notice that in all the examples above, profit is the motive for preservation. The mountains’ beauty is being packaged, advertised, and rented out. That’s not to blame Milo Smith, or even the wealthier ski developers: they needed a way to earn a living, and the result was a healthier ecosystem. But their scenery-based businesses serve as a baseline to measure a certain transformation. By the turn of the century, that subterranean yet powerful force — public sentiment — was changing in ways that had a profound impact on the Taconics.

John Muir must be mentioned as the avatar of this shift. More than anyone, he successfully pioneered and publicized the concept that natural beauty had value in and of itself, never mind commercial worth. In a 1912 letter written as part of his famous struggle to protect the Hetch Hetchy Valley in California, he deplored those who were “eagerly trying to make everything dollarable.” He compared his beloved valley to the Jerusalem temple that Jesus fought to save from the money lenders, and eloquently recorded his core belief: “It is impossible to overestimate the value of wild mountains and mountain temples as places for people to grow in, recreation grounds for soul and body.”

He got the ear, most importantly, of Theodore Roosevelt, but I wonder if his words — or at least his sentiments — reached the ears of influential men in the Taconics. In 1908, Massachusetts established a Mount Everett Reservation Commission, “authorized to take, or acquire by purchase, or gift, land situated in the Mount Everett Mountain Range.” $5,000 was set aside for this purpose. This initiative did not stem primarily from any practical concern (such as fire suppression) but from the desire to protect a mountain whose “…dome dominates the landscape of the South Berksires like a mighty sentinel.” The time had come to save beauty.

But preservation proved no easier then than now; while the Commission quickly bought 400 acres on the north slope of Everett (from OC Whitbeck for $1500) and a nearby 125 acres for $500, it stumbled when it used eminent domain to claim a tract on the west slope that included “Undine Lake.” (Guilder Pond today.). The owner, James McNaughton, sued, claiming he’d been given unfair value, and citing the Whitbeck property as a comparable. But the Judge ruled that no comparison could be made because the worth of the McNaughton land “did not consist so much in the land itself as in its sentimental value … as a sight-seeing place.” So McNaughton had to eat his price. But it’s worth noting that in 1915 a court recognized that land could have a value purely aesthetic.

The efforts of Massachusetts to preserve its mountain lands were aided, around 1898, by the water levels of Berkshire streams.

Why? Because a New York wool merchant named Frederick Masters was an avid fly fisherman. His grandson Edgar describes him as a tie-your-own-flies purist with waders and a wicker basket. But in the spring of ’98, the Massachusetts streams he loved to visit were dry, and someone suggested he go “over the hill” — past the site of today’s Catamount (then known as Molasses Hill) to Copake Falls, where rains had been more consistent. Masters took to the area, had some drinks at the Taconic Wayside Inn, and met local store owner Thomas Keating, who told him of an abandoned farm in a nearby valley known, for some reason, as “Little Europe.” (A local iron worker used to finish his drinks at the Inn with the proclamation: “I’m going to Little Europe,” climb the hill, and sleep there in abandoned barns.) In a horse and buggy, Keating took Masters to view the property; Frederick immediately noticed the steady springs and, envisioning trout ponds, bought the land from the iron works owners (whose furnace was still an immediate neighbor.) By the 1920s he’d built what his grandson describes as a “gentleman’s summer home” constructed of chestnut.

By this time the spirit of Muir had begun to shape the priorities of powerful New Yorkers, including then Governor Al Smith, future Governor Franklin Roosevelt, and Robert Moses, who had established and put under his power a New York State Park Commission. Roosevelt, who grew up in Dutchess County, dreamed of a motorway connecting parks along the east side of the Hudson Valley, like a string threading beads. In 1922, as part of a State Park Plan, a tri-state park was proposed, imagined to contain all the long-admired beauties of the Taconics. (Taconic State Parkway was originally meant to swing closer to the border.) The Plan looked at the Taconics as a “splendid opportunity,” shown plainly if you put together maps and “see the significance of this mountain mass.”It would encompass 20,000 acres in Massachusetts, 11,000 in Connecticut, and 9,000 in New York. Rather bluntly, the Plan described the New York area as “… not of any value in itself but western slopes are needed for fire protection and no one state can do it.” One problem foreseen: “The greater part of public use will come from New York while greater cost of purchase and development falls on Connecticut and Massachusetts.” Neither of New York’s neighbors wanted to appropriate money for use in other states. But in 1925 the State Legislature created the Taconic Park Commission to help move this vision forward. Roosevelt and Masters were members, Roosevelt chair.

The first parcel deeded over to this burgeoning project was 38 acres along North Mountain Road, belonging to Frederick Masters. But the centerpiece of the Tri-State Park vision was the eighty foot Bash Bish torrent. It crashes and spills in Massachusetts, but the only practical access came through New York, past the site of the vanished Swiss chalet / hotel. So Masters bought about 200 acres necessary to save the entire area. He held it in his wife’s name for a few years, and sold it at cost, with a proviso that it be held public forever.

While a formal tri-state park has never been established, the intent has succeeded. Massachusetts steadily put the pieces together, beginning with the 1924 creation of a 424 acre Bash Bish State Park based on Masters’ donation. By 1968, gifts from the Van Der Smissen family allowed for the 4,619 acre Mount Washington State Forest (including the summit of Alander). Jug End Reservation was added in 1994. By the time its original Commission was disbanded in 1975, Mount Everett Reservation had reached 2,492 acres. For its part, New York has added to Taconic State Park until its 5800 acres form a protected strip along the western flank of the mountains.

That 1908 Commission saw well beyond the slopes of Everett, believing that “… the possibilities of the territory” were “magnificent in their extensive scope.” Their hopes have been borne out. The 19th century notion that nature owned inherent value — and that government played the key role in preserving it — has held, and grown, through the decades.

But there’s a bit of irony behind this shift in public feeling. One crucial underpinning is, of all things, the invention of the automobile. Raymond Torrey, author of a 1926 study of potential state parks, was clear-eyed on this: he saw that the environmental movement in New York was “accelerated by nationwide conservation influences” but also by the “immense increase in outdoor life due largely to the invention and perfection of the automobile.” Like Robert Moses, he believed that “Highway and park development went together.” At a 1948 meeting of the Taconic State Park Commission, Francis Masters and others noted that: “Forty years and more ago, the rugged hills were more frequented; lovers of nature drove through in weekend jaunts with horse and buggy.” But visits — at mid-century — were down because “automobiles don’t take to rough dirt roads.” So park development meant road paving. Those pioneers can hardly be blamed for lacking a crystal ball, but a century of carbon emissions has not been kind to the mountains they loved.

What use do we make of used-up but lovely land? The story of the Taconics illustrates several answers. One: deploy it for commercial gain, as with boarding houses and ski areas. Two: use government to protect it and open it to all comers.

Three: allow private conservation groups to fill in the gaps left from government purchases. Today, the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Nature Conservancy maintain important pieces of mountain land, and the Appalachian Trail, which leads from Lion’s Head to Jug End, is federally protected.

Four: build summer camps. These are private ventures, of course, but are steered by a public mission. Camp Hi-Rock, established on land around Plantain Pond in 1948, declares its purpose as: “the growth and development of the spirit, minds and bodies of the participants we serve.” The leaders (from the Bridgeport, Connecticut YMCA Chapter) who found the land and built the camp were guided by the faith that a site in the wilderness was ideal, that there was an intrinsic value in introducing young people to nature.

Northrop Camp, which operated for seventy years until a 1993 fire destroyed its main building, is a particularly inspiring story. A New York botany professor, Alice Rich Northrop, decided in the early 1920s that the city schools failed to offer any thorough study of nature or ecology. So she planned to turn her property on East Street in Mount Washington into a summer nature camp for underprivileged city kids. But in 1922, driving upstate to make final preparations for the initial season, her car stalled on railroad tracks. She was hit and killed.

This didn’t stop her friends from opening the camp the next summer, with two groups of twenty boys sleeping in tents, using an old barn for a rec hall, and washing with cold water in an old shed. The next summer’s campers were two groups of girls. Despite — maybe because of — the spartan conditions, the Northrop experience changed many lives. Recollections, from decades later, testify that campers came “to know that there is a beautiful world beyond the concrete caves we call home” or learned that “rain, wind, stars and moon were part of me.” One believed that a “Deep love of nature and creations’ wholeness fostered in three short summers has enlightened me all my life.” They studied plants, met raccoons face to face, and at least once cooked and (tried) to eat rattlesnake. The trail from the Northrop site to Bash Bish falls, blazed by can lids nailed to trees, can still be followed. In recent years, led by alums, the camp has been partially rebuilt and short camping sessions have been revived.

A fifth approach to the “What use?” question can be found in Connecticut. Judge Donald Warner, a prominent citizen of Salisbury, began buying lands around the abandoned Mount Riga furnace in the late 1800s. He’d lend money to colliers who were still working the mountains, enabling them to buy ten or so acres at a time. Once they’d harvested all the useful timber, Warner would buy the land back, and so steadily increased his holdings. In 1896 Warner learned that the local bank held tax liens from the Millerton Iron Company, which at that point owned the old furnace lands. He was able to cheaply purchase about 5,000 acres in Mount Riga. But, moved perhaps in part by the tax burden of so much property, Warner looked for partners. In 1922, three families —the Warners, McCabes and Schwabs, all interconnected by business and marriage —- formed a corporation to control the property. These families already had smaller holdings on which they’d built “camps.” The McCabe version boasted a barn, main cabin, and satellite cabins constructed of chestnut.

This was the basis of Mount Riga Incorporated. It was — unusually at the time — set up as a for-profit land-holding company. Land was controlled by the Corporation, but lease-holds were sold, so houses could change hands. Eventually about 350 people formed a seasonal community, in homes that lacked electricity and in some cases running water.

This remote society was threatened in the 1950s, when the state of Connecticut (finally) decided to help form that Tri-State Park proposed in the 20s. (Apparently the indefatigable Robert Moses had begun to push the idea again.) New York promised to buy 1,000 acres in the Taconics to add to the project. But Salisbury rebelled. Led by State Representative Jack Rand, they lobbied Hartford, arguing in part that it was wasteful to, as one citizen remembered, “spend state money for land way out in the sticks.” At one point, Dan Brazee even brought his pet deer to Hartford and declared that this Tri-State Park idea would deprive Bambi of its home. (Though wouldn’t Bambi be at home in a state park?). In the event, Hartford backed down, though many thought this had less to do with Bambi and more with the tight purse-strings of state government.

This eliminated the threat of a state takeover, but financial problems plagued Mount Riga — until it was rescued by the Appalachian Trail. That famous footpath begins in Georgia, ends in Maine, and along its fifteen mile traverse of the South Taconics climbs up and down Lions Head and Bear Mountain, dips into Sages Ravine, and ascends and descends Race Mountain, Mount Everett and Jug End.

Under the Carter administration, the A.T. came under federal protection: prior to this, much of its route had depended on the goodwill of many different landowners. The Mount Riga Corporation owned most of the trail’s route in the Connecticut part of the Taconics, and the sale of this land to the state raised over a million dollars that enabled the Corporation to, among other things, make repairs to the Riga Lake dam. Corporation member Charles Vail characterized the A.T. sale as a “win-win” that allowed the Mount Riga community to restore and maintain its property.

Oral histories collected by the Salisbury Association preserve fond memories of Mount Riga that reach a hundred years into the past. Gustav Schwab recalled hiking, at night, from Riga Lake to the “western lookout” (now the intersection of the South Taconic Trail and Quarry Hill Trail) where he and his friends watched the trains in the valley below. When they saw steam rise from a locomotive, they’d count the seconds until the noise reached them. Mike McCabe remembers, in the 1940s and 50s, using a pony and cart to collect garbage from fifteen different camps, and feeding it to pigs who were kept on the mountain. Dan Brazee, caretaker in the 1950s, rescued a young deer from dogs and raised it as a pet (the Bambi who eventually lobbied Hartford.)

Today Mount Riga Incorporated is still a private enclave, but anyone can apply for permission to camp there or swim the lake. In the 1980s, the group donated, to the Nature Conservancy, land around Bingham Pond Bog (a haven for rare plant species) and also Bald Peak. In 2008, a deal with the Nature Conservancy allowed the South Taconic Trail to extend to Rudd Pond.

In 2009, in a talk on the history of Mount Riga, summer resident Jim Dresser characterized the appeal of the off-the- grid lifestyle of the camps: “Mount Riga’s current culture tosses a monkey wrench into the engine of so-called progress.” Camp owners “simply refuse to stay on the escalator carrying our society to greater creature comforts.”

Today the railroad, the boarding houses, many of the camps and resorts are vanished. But the Miss Sedgwicks of the world still find the South Taconics, still seek a ready encounter with nature. The internet lets them tell the world what they find, but perhaps the inner experience is as quiet as ever.

(Note: Thanks to Mount Washington Historical Society for research, advice and image sharing)